Chaparral: A Desert Herb with a Remarkable Story

Share

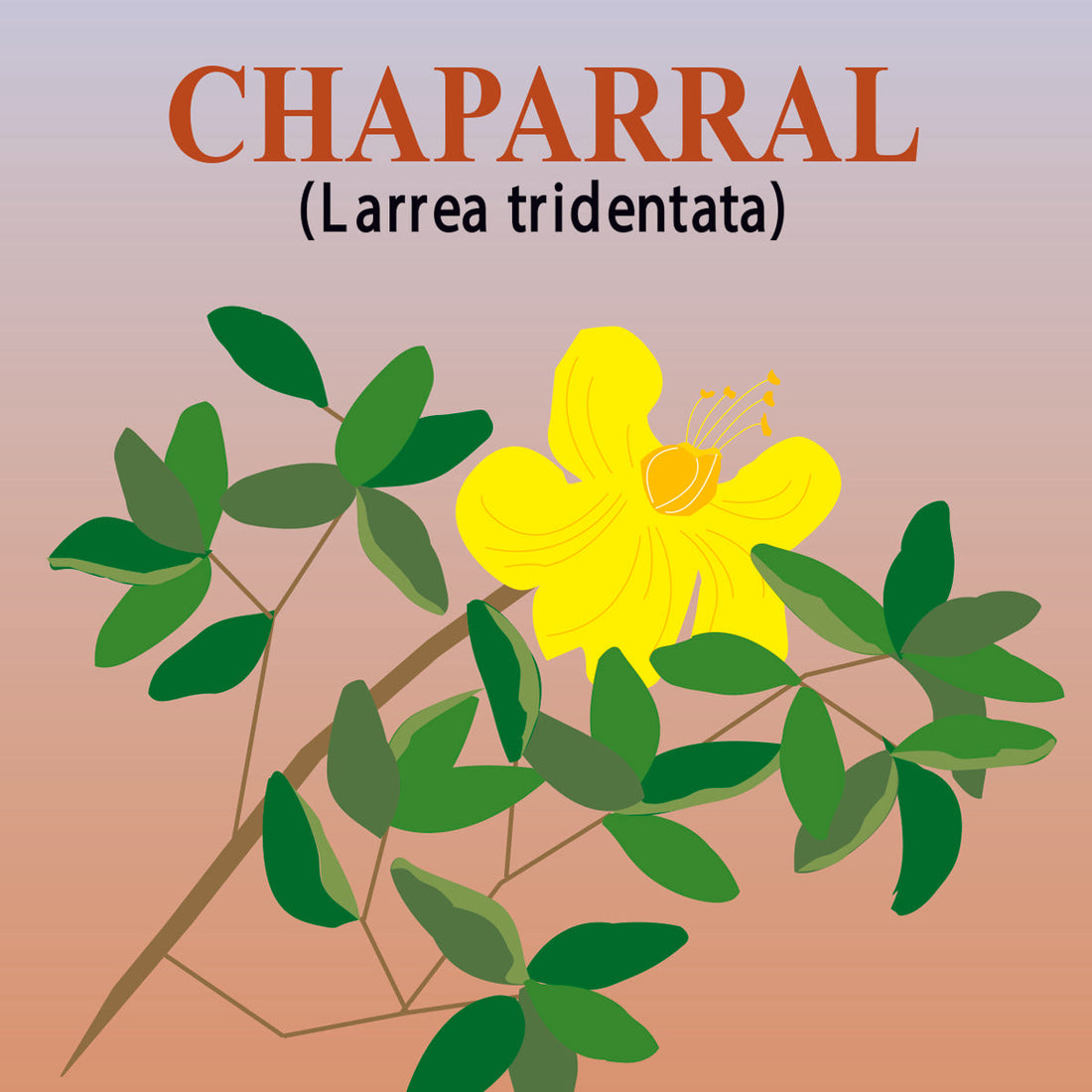

Chaparral (Larrea tridentata), also called creosote bush, is a tough, sun-loving shrub found across the deserts of Arizona, California, Nevada, and northern Mexico. A hardy desert plant, chaparral has been used for generations in traditional herbal practices — and continues to attract interest from scientists for its unique chemical profile, particularly the compound NDGA.

Traditional Uses of Chaparral

Chaparral has long been a cornerstone of traditional herbal practices among Indigenous peoples of the American Southwest. Tribes such as the Cahuilla, Pima, Yaqui, and Seri incorporated chaparral into their daily and ceremonial lives in a variety of ways. The plant was not merely a practical resource; it was understood through generations of observation and passed-down knowledge to have remarkable capabilities.

The most common traditional uses included:

- Topical poultices made by crushing fresh or rehydrated chaparral leaves and applying them directly to the skin, often wrapped in cloth or plant fiber.

- Herbal teas prepared by steeping dried leaves and twigs in hot water.

- Steam inhalation using chaparral-infused water, which was part of sweat lodge rituals or used to clear the head and breathing pathways.

- Chaparral smoke and resins were also burned in cleansing rituals or to ward off pests.

These uses reflected a deep respect for - and understanding of - the plant's power. Chaparral's traditional uses helped pave the way for the scientific research of today.

Scientific Interest: What’s in Chaparral?

Modern science has taken a strong interest in chaparral, primarily due to its complex chemistry and the presence of nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA), a potent plant-based lignan found in high concentrations in chaparral leaves.

NDGA has been studied for decades, and its activity has been observed in several key areas:

- Antioxidant Activity - NDGA is recognized as a powerful antioxidant. Laboratory studies have shown that it effectively scavenges free radicals and inhibits lipid peroxidation — both key processes related to oxidative stress. This antioxidant behavior has made NDGA a candidate for research into how plants protect themselves from environmental damage.

- Antiviral and Antifungal - In vitro studies have evaluated NDGA’s effect on a variety of viral and fungal organisms. Researchers have tested chaparral extracts and isolated NDGA for potential interference with viral replication cycles, noting marked inhibition of cell proliferation, especially on certain types of viruses. Studies have shown similar activity and ability in fungal cell walls.

- Antineoplastic Research - NDGA has also been studied for its ability to affect cell signaling pathways associated with abnormal or uncontrolled cell growth. Preclinical research has investigated how NDGA interacts with enzymes such as tyrosine kinases, which are involved in the regulation of cell proliferation. These findings have made NDGA a point of interest in experimental oncology, being the subject of many further studies and clinical trials.

- Enzyme Modulation and Anti-Inflammation - NDGA has been explored for its influence on a variety of biological processes, including inflammation pathways, metabolic enzymes, and hormonal signaling.

About NDGA and Safety

Because NDGA is a highly active compound, safety and dosage are critical. Chaparral and NDGA are potent and should not be taken in excess. Professional medical advice is recommended before using chaparral if you have a history of liver or kidney disease.

The Plant That Lives for Millennia

Chaparral isn’t just powerful — it’s ancient. In the Mojave Desert of California, scientists have identified a clonal colony of chaparral known as "King Clone," which is estimated to be over 11,000 years old. This means the same genetic plant has been growing, regenerating, and spreading in the same location since before the rise of agriculture.

Clonal colonies like this one spread slowly by producing genetically identical offshoots from a parent plant. Over time, the original plant dies, but its copies live on, forming a slowly expanding ring. The longevity of chaparral is a reflection of its incredible ability to survive in harsh desert conditions — including drought, extreme heat, and nutrient-poor soils.

This kind of survival isn't just biological; it’s symbolic. To many cultures in the Southwest, chaparral represents vitality, adaptability and continuity across generations.

Conclusion

Larrea tridentata, or chaparral, is a desert native with an extraordinary story. From its time-honored role in Indigenous cultures to its place in the laboratory, chaparral continues to fascinate herbalists, researchers, and desert dwellers alike.

Its powerful chemistry, especially the activity of NDGA, has sparked both excitement and caution in the scientific community. And its resilience in the desert makes it one of the most enduring plants on Earth.

As with any potent herb, chaparral should be approached with respect, knowledge, and care. But for those who take the time to learn its story, it offers a remarkable window into the ancient relationship between humans and plants.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not offer medical advice. Chaparral is not approved to diagnose, treat, or prevent any disease. Please consult a qualified health professional before using herbal products, especially if you are pregnant, nursing, or taking medication.